Introduction

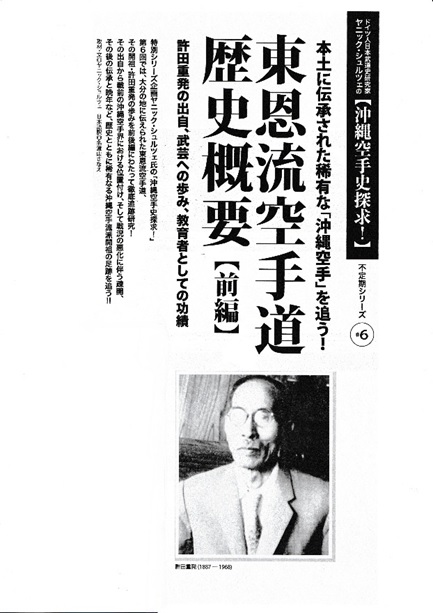

This upcoming book offers a concise yet in-depth historical study of Gōjū-ryū Karate, tracing its development from Naha-te to its formal recognition in the modern era. Focusing on the lives and teachings of Higaonna Kanryō and Miyagi Chōjun, it explores training methods, naming processes, and the cultural exchange between Okinawa, Japan, and China.

Based on primary sources and long-term research, this work goes beyond simplified lineage narratives and presents new perspectives of interest to serious practitioners and historians alike.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction

What is Gōjū-ryū?

Higaonna Kanryō and Naha-te

The Naming of Gōjū-ryū

Chapter 2: Training in Naha-te

Becoming a Student of Higaonna Kanryō

Training

Military Service

The Passing of Kanryō

Chapter 3: The Formation of Gōjū-ryū — Chōjun during the Taishō Period

Fuzhou

Training Alone

Okinawa Karate Club

Chapter 4: The Great Leap Forward — Naming of Gōjūkai

To the Mainland

Adopting the Name Gōjū-ryū

From Chinese Hand to Empty Hand

Popularization

Chapter 5: The Man Miyagi Chōjun — From Wartime to Postwar

World War II

Chōjun’s Family

Chōjun, the Okinawan

Chōjun, the Martial Artist

Chapter 6: At the End of the Series

Report on Visiting the Jīng Wǔ Athletic Association (Special Edition)

About Higaonna Kanryō

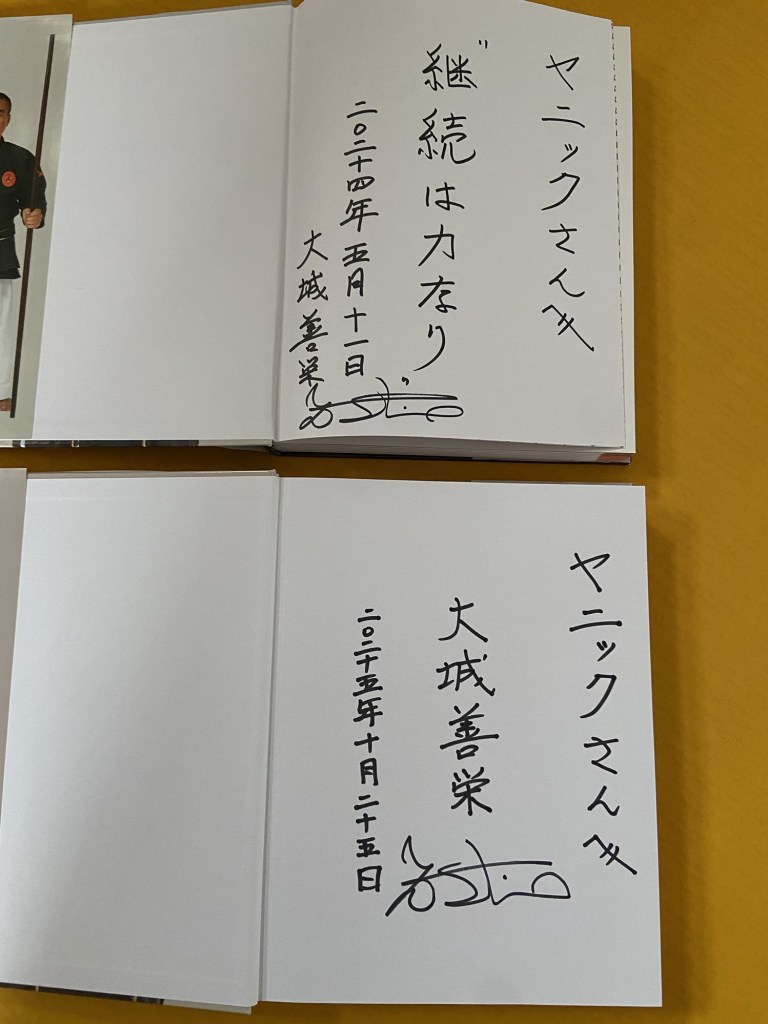

Limited Edition

Limited Edition

A limited edition will include three exclusive additional chapters that will not appear in the later standard edition, making it a unique release for collectors and dedicated readers.

The limited edition will be strictly limited to no more than 200 copies. Pre-orders may be placed directly with me via my website or Facebook. Once an approximate publication date is available, further details regarding the ordering process will be communicated via Messenger or email.