A few days ago, I wrote a short article about the different ways to write Kōdōkan, and I’d now like to draw attention to a similar case – this time concerning Shōrin – which also comes with varying readings.

1. 小林流 – Shōrin-ryū / Kobayashi-ryū

Reading:

- 小 (shō) → small

- On-yomi: shō

- Kun-yomi: chiisai

- 林 (rin) → forest

- On-yomi: rin

- Kun-yomi: hayashi

- 流 (ryū) → style / school / stream

Meaning: „Style of the small forest“

Origin / Context:

This writing is typical for the Shōrin-ryū style of Okinawan Karate founded by Chibana Chōshin (1885–1969). The kanji were deliberately chosen to evoke a connection to the Chinese Shaolin, but use different characters that are more familiar in Japanese and perhaps stylistically softer. Chibana also wanted to emphasize his own interpretation through this choice.

2. 少林流 – Shōrin-ryū / Sukunaihayashi-ryū

Reading:

- 少 (shō) → few, young

- On-yomi: shō

- Kun-yomi: sukunai, sukoshi

- 林 (rin) → forest

- 流 (ryū) → style / school

Meaning: „Style of Shaolin“ (literally: „Style of the young forest“)

Origin / Context:

This is the classical Chinese writing for Shaolin – 少林 (Shàolín in Chinese). In Japanese, it is also read Shōrin. This version appears in more historically or Chinese-oriented contexts, such as when emphasizing the origin from the Shaolin Temple.

In Okinawan Karate, this writing is used in styles that trace back to Kyan Chōtoku, such as Shōrin-ryū Seibukan (Shimabukuro Zenryō) and Shōrinji-ryū (Nakazato Jōen).

3. 松林流 – Shōrin-ryū / Matsubayashi-ryū

Reading:

- 松 (shō / matsu) → pine (tree)

- On-yomi: shō

- Kun-yomi: matsu

- 林 (rin) → forest

- 流 (ryū) → style / school

Meaning: „Style of the pine forest“

Origin / Context:

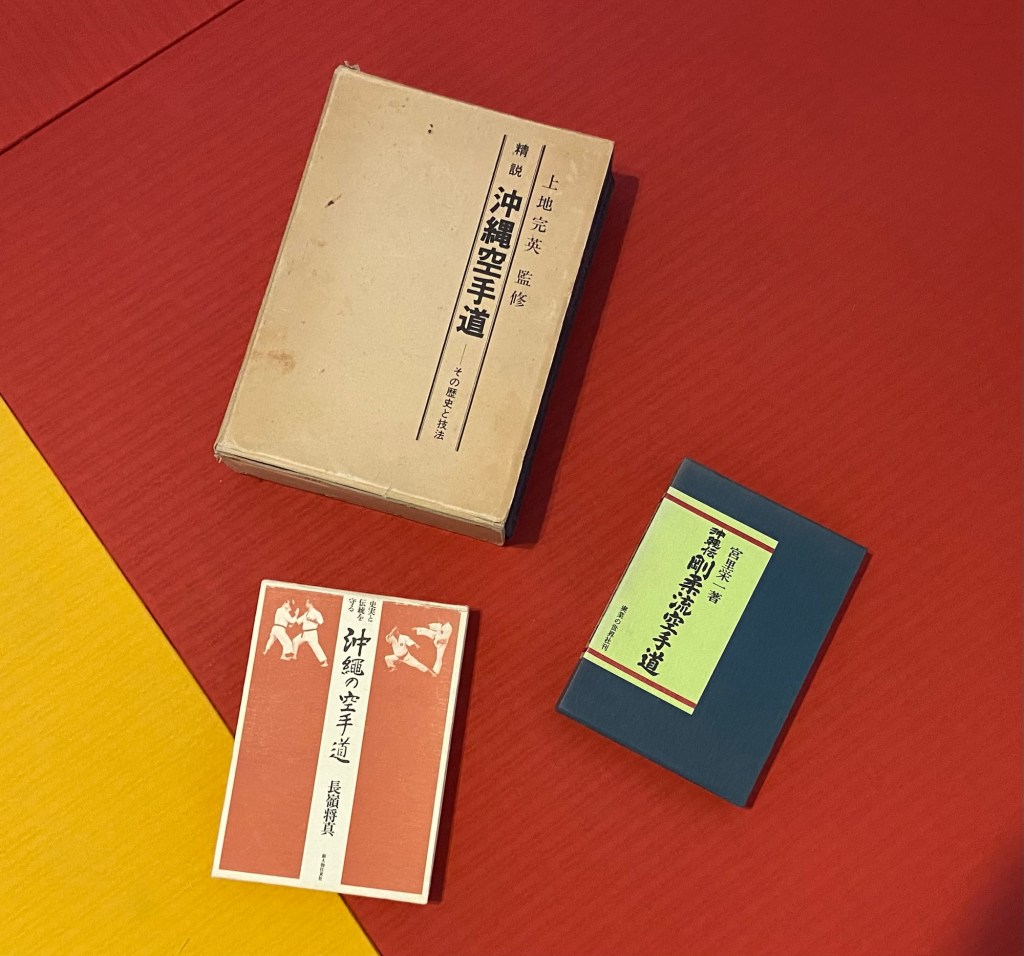

This variant is used in Matsubayashi-ryū, founded by Nagamine Shōshin. „Matsubayashi“ is an alternative reading of the kanji for Shōrin (松林). The name was intentionally chosen as an homage to Matsumora Kōsaku and Matsumura Sōkon, while matsu (pine) is also a symbol of constancy and purity.

Some schools pronounce this writing as Shōrin-ryū, others as Matsubayashi-ryū, depending on how they emphasize their stylistic heritage. In Western literature, both versions are commonly found – for example, Matsubayashi Shōrin-ryū.

An Exception: 書林 – Shorin

This writing appears in an English-language publication where I once mistakenly read it as Shōrin.

書林 – Shorin

Reading (On-yomi):

- 書 (sho) – book, writing, script

- 林 (rin) – forest, grove

Meaning:

- Literally: “Forest of books” or “Grove of writings”

- Figuratively: publisher, bookshop, place of literature

The term 書林 is also used metaphorically in classical Japanese and Chinese literature to denote:

- a place of learning

- a center of literary activity

- or even a printing house or publishing establishment, particularly during the Edo period (e.g., as a synonym for a book publisher or bookshop)

A well-known bookshop in Okinawa also uses this writing: Gajumaru Shorin / Yōju Shorin (榕樹書林).