Exactly one month ago today, I learned of the passing of Yogi Josei Sensei. Miguel R. informed me of this sad news via Facebook Messenger. I made the personal decision to wait a month before writing down my thoughts — my prayers were already directed on the day of the news to his soul, to his family, and to the students of Yogi Sensei.

Before I met Yogi Sensei for the first time in 2008, I had already heard many stories about him, all describing his compassionate character. So, when I finally met him in 2008, it wasn’t much of a surprise.

At that time, Jhonny Bernaschewice allowed me to travel with him and his group to Okinawa. We flew from Frankfurt am Main via Taipei to Okinawa, where we had the opportunity to train for nine days under Gakiya Yoshiaki and Yogi Josei. Since I had only started practicing Okinawa Kobudō in 2007, I began with the Hojo Undō (1–3) and the kata Shūshi no Kon. From there, I trained directly under Yogi Sensei, while the advanced students continued practicing higher kata with Gakiya Sensei. Yogi began to intensively teach me Shūshi no Kon.

On the first day, we met Gakiya and Yogi directly at the Budōkan, and from the second day on, Yogi began picking us up from our accommodation. Every time, he arrived in his “Nissan Scout,” loaded all the bō into the car, and drove me to the Budōkan. During the drive and in the parking lot, he would tell me many stories from his youth in Okinawa — for example, how American soldiers provided him with chocolate after the war — a story quite similar to one I heard from my grandfather, who was also given chocolate by English soldiers. Yogi Sensei also told me how Heiwa-Dōri was once underwater and how shopping there was no longer possible.

A few times, he would open his trunk and give me two gifts — one for Jhonny Sensei and one for me. This is how I, among other things, had the honor of receiving a program booklet from the memorial ceremony for Itokazu Seiki Sensei, the father of Itokazu Seishō Sensei.

After every training trip, Yogi would take us to the airport. He always struggled to hold back tears — saying goodbye was hard for him each time, and he looked forward to seeing us all again the following year.

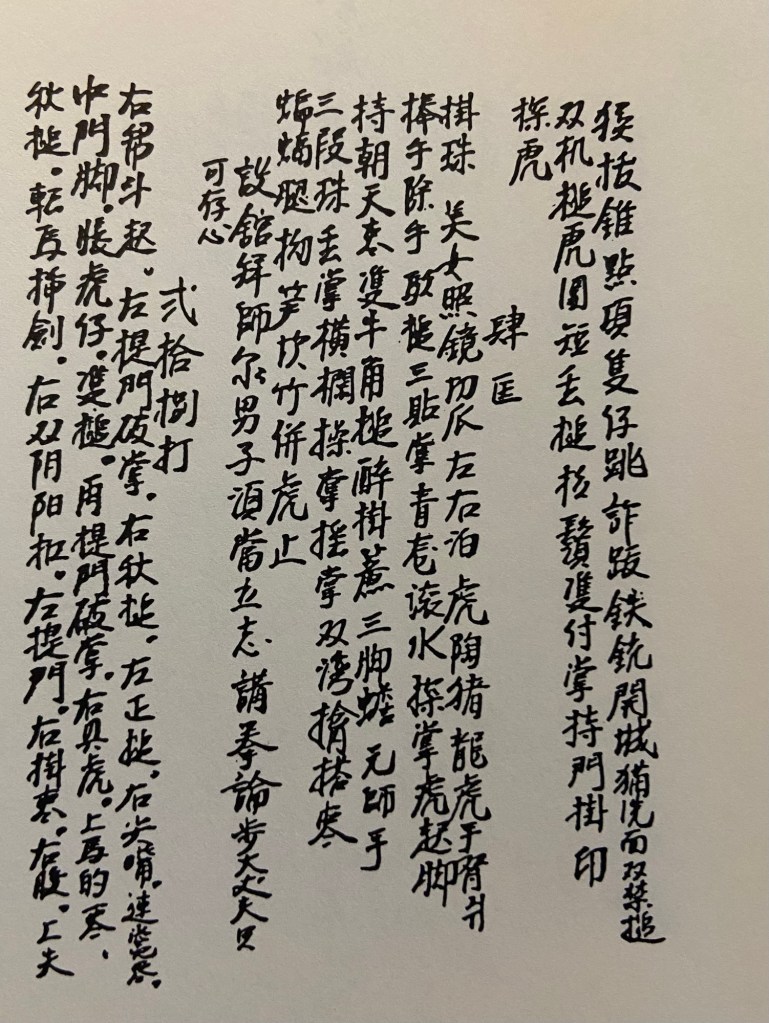

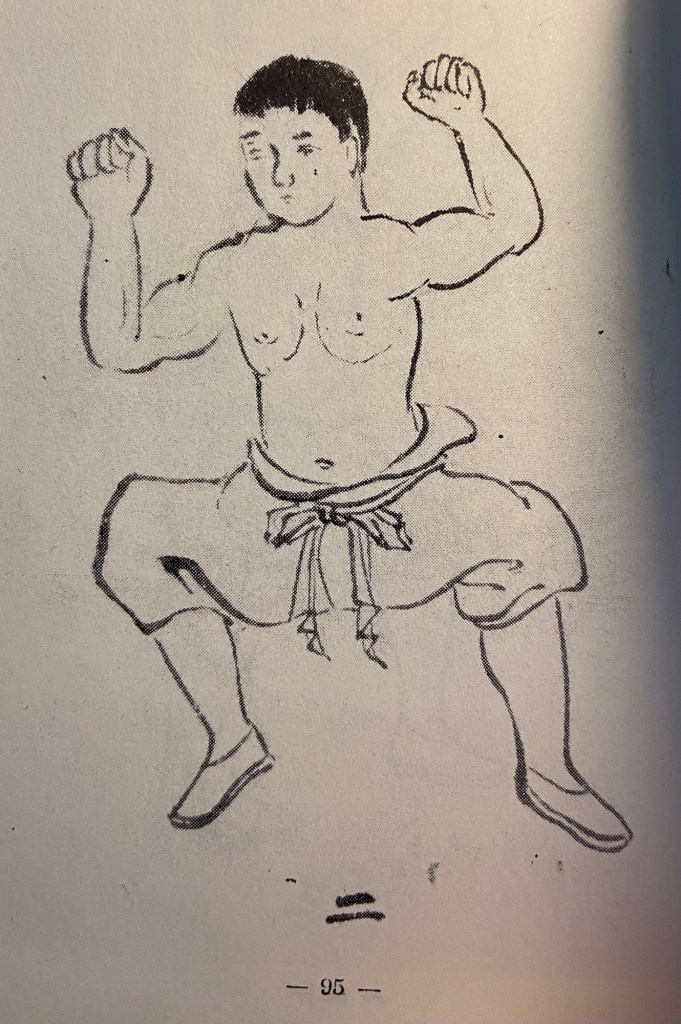

After Gakiya Sensei fell ill, Yogi took over sole training of our group for the first time. There were a few changes in some kata — Yogi began teaching his own interpretation of Kobudō and also founded his own organization: Okinawa Kobudō Renseikai. After consulting with Jhonny, I began traveling to Okinawa independently from 2012 onwards, and over the next two years, I received, among other things, private lessons from Yogi Sensei. He taught me his Nunti-kata, Ufuton-bō, and his Jō-kata, and continued to train me intensively in other weapons (Bō, Sai, Tunkwā, Nunchaku, Eku).

We practiced the Nunti-kata at the time with my rattan bō, which had a point on one end. Yogi explained this as the spear tip. The first few times, he would always laugh when the spear tip wasn’t in the correct position at the end of the kata.

Once, while eating at an Okinawan restaurant, he asked me if I knew “Ashi-sumō,” and he began to practice it with me. According to him, he had already practiced it as a child with other kids.

The last time I saw Yogi Sensei was at the Budōkan in 2024. He told us about his Beiju celebration (88th birthday), and I met his son for the first time, who continued to drive him to the Budōkan every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday so that Yogi Sensei could continue to follow his calling.

Sensei-ni-rei